The Poor Can’t Afford the Benefits of Monogamy, and the Rich Don’t Need Them

The rich flaunt non-monogamy, while the poor stopped marrying. To understand, consider monogamy a technology.

Polyamory is back in the news, again. It happens every couple years, like clockwork. I’m used to it, having been non-monogamous myself for ten years and therefore always sent the articles both by the algorithms and friends. But there is one difference this time around: nowadays, the articles tend to include an analysis of class.

Consider the recent piece by literary scholar and professor Tyler Austin Harper. In it he reviews a recent memoir, More, which depicts a particularly cringeworthy non-monogamous experience for one wealthy New Yorker. His piece paints a picture of a particular kind of well-publicised polyamory, the “ruling classes’ latest fad,” a self-indulgent lifestyle choice complete with its own therapeutic jargon. It is, he suggests, something only for the sort of upper-class folks who have "disposable income and time—to pay babysitters and pencil in their panoply of paramours—that are foreclosed to the laboring masses." Harper’s piece is snarky, fun, even for someone like me. I couldn’t help but smile and nod with recognition—I have seen some of what he describes in my social world.

And yet. There’s more to the picture. For the class commentary on non-monogamy isn’t just about the rich these days; at the other end of the spectrum, economists openly worry about the lack of monogamy for those labouring masses presumed to be deprived of babysitters. Melissa S. Kearney has for example recently written about how two-parent families are measurably better for children than single parents, praising the economic and developmental benefits of a particular family structure and (this bit mostly implied) monogamy itself.

Both of these “takes” contain some elements of truth. Rich people doing polyamory can be a cringe-inducing, navel-gazing affair, in which people lucky enough to afford all the trappings of traditional family immediately throw these off, declaring themselves liberated. And children with a greater number of parents do better (though not, I’d suggest, because of any God-ordained need for a mother-father duo, but because they are, on average, given more time, attention, and resources from less stressed and traumatised people). Despite all this, and despite the way many recent writers focus closely on class in their arguments, so many takes ultimately miss the underlying relationship between class and family structure. And this, in turn, means they miss the greater challenge: a vast ongoing economic shift which means we must navigate questions of social reproduction anew, not merely turn back to old norms.

In other words, I’m so glad people are finally talking about monogamy and class in the same thought pieces, but: let’s take it further.

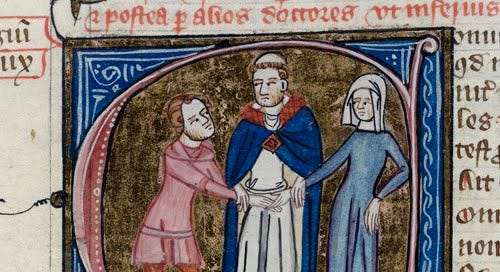

For monogamy is not simply a personal lifestyle choice. It is more accurate and illuminating in this context to see it as a sort of socio-cultural technology, a mechanism designed and regularly re-designed by humans to perform specific functions. I’m using the term technology here, despite my general suspicion of both technological solutions and technology enthusiasts, because I want to emphasise the way monogamy is not just a socially-sanctioned and enforced practice, but something that performs particular designated functions for those who adopt it, and which then structures other downstream human behaviours. Like software, it gets constantly updated, legally, culturally, and otherwise. For example, sometimes monogamy has really just meant sexual loyalty for the women involved, sometimes it means lifelong monogamy for both parties, sometimes it means serial monogamy with many relationships throughout the life cycle. Think of the Hebrew Bible and its many concubines and wives, versus the American Evangelical Christian obsession with lifelong monogamy for both parties. For that matter, think of Evangelical Christians versus the norms of The Jersey Shore.

I’ve also used this term, “socio-cultural technology”, because I want to emphasise that like all technologies monogamy can be used by those who encounter it in different ways, and with different effects. (And I’m not using the terms “social technology” or “cultural technology” because these have already been used in academic literature to refer to rather different things).

Which leads to the question: what exactly does monogamy “do”, as a technology of sorts, not just for the individual, but for society?

Well, there’s really too much to say in a blog post, but let’s have a quick scan. Monogamy as a socio-cultural technology has traditionally been used to engineer social reproduction, a jargony Marxian term which really just means everything that keeps society functioning in its current arrangement (as opposed to the forces that produce new things). Defined broadly, social reproduction includes the ongoing reproduction of human beings, both sexually and in terms of keeping them going day to day. Social reproduction involves both laundry and emotional care, informal knowledge transfer and formal education, and the passing on of both tradition and material property/legal titles. It is often highly undervalued, especially since it involves a lot of unpaid work by women, yet it is critically important, for it is what allows society to keep going at all. And notably, it is generally what helps rich people stay rich generation to generation, and poor people stay poor.1

Like all technologies, the socio-cultural technology of monogamy makes some things easier and other things less so; it re-organises our world of possibilities and “affordances,” the action-possibilities afforded to us. These affordances have their varied downstream consequences, of course, just as cell phones, or the internet, do, none of which are intrinsically good or bad but all of which matter. The best phrase I’ve heard on this comes from the American Historian Melvin Kranzberg, who wrote: “Technology is neither good nor bad, nor is it neutral.” Monogamy too is neither good nor bad, but nor is it neutral, in that it enables and makes easiest and enforces certain kinds of arrangements for the reproduction of human beings and their daily life.2 It has done this continuously and powerfully throughout history.

For example, in a book I frequently cite about the “WEIRD”ness of Western psychology, Joseph Heinrich’s The Weirdest People in the World: How Westerners Became Psychologically Peculiar and Peculiarly Prosperous, the author argues that the Catholic church remade family norms over centuries, often while encountering massive resistance, in order to break down the power of larger family units and instead strengthen the power of the Church. Not only did the Catholic church prevent men taking second wives and informal concubines, but it stopped the formal recognition of bastard children, marriage between cousins (previously popular!), adoption practices, and more or less anything that aided in building the types of dense kinship networks that are still part of much of the rest of the world’s values. Monogamy was just one pillar of a larger “Marriage and Family Plan” designed by the church to restructure families, but it was a powerful component. It helped the Catholic church break up powerful clans and ultimately consolidate power, while entirely restructuring kinship and sexuality along the way.

The result is, in many ways, where we’re at today: small nuclear families, tons of people living alone, many people who don’t even know their cousins and certainly wouldn’t marry them. Henrich notes that by the time Protestantism, the “WEIRDest religion” came along, the family had been broken up into the nuclear family and individuals were ready, culturally and psychologically, to work for their salvation in small units and ultimately compete under capitalism.3 There was also the added benefit that monogamy tends to allow even low-status men wives, which, Henrich argues, makes men overall more peaceful. There are absolutely a bunch of issues with this book, the discussion of which must wait for another day. But the point, for now, is that even if Henrich’s account is only partially accurate, it shows how monogamy functions as a technology, and can be reshaped in order to alter the social fabric.

And this is why it is useful to ask what monogamy does. Monogamy has been (increasingly) tying men and women into a very specific kind of closed family unit.4 This kind of family unit makes spouses responsible for each other both in terms of care and finances: and generally responsible for and to each other first rather than anyone else, that is, including their larger communities and the state. Indeed some writers and historians argue the family-form has often been engineered and enforced and reinforced legally precisely at the moment when the state wishes to take less responsibility for people’s overall well-being and/or their debt.

Perhaps most obviously, monogamy has been both encouraged and enforced because it similarly makes people responsible for their biological offspring. Specifically, various forms of monogamy and its social/legal instantiation, marriage, have (for far longer than the lifespan of state poor-laws or even the Catholic Church) both enabled and enforced a particular means of exchange, which generally looks like this: women perform both sexual- and social-reproductive work, while men provide economically in other ways.5 Monogamy keeps the exchange working both because of the supposed guarantee of DNA transmission and the shame should anyone leave the arrangement lightly. This exchange privatises otherwise social responsibilities and problems, induces people to work in a particular way to keep their tiny personal island from sinking, enables relatively orderly social reproduction, and for the most part assigns parental responsibilities in this largely-still-gendered way.

I list these points not to condemn them (though they can be profoundly oppressive) but to point out the usefulness of monogamy. It is boring to argue (as certain writers do) about whether monogamy is “natural”; what is both more evident and more explanatory is that it is useful. It creates a social order, one that helps many agents, including the men and women (and others) who practice it, achieve particular goals.

To say all this about monogamy and class and “social reproduction” and history and “usefulness” is not, of course, to deny that some people truly prefer monogamy for emotional reasons, or to suggest this labour-exchange and its practical utility is always at the front of people's minds when they consider their love lives. This is generally not what people are thinking about Valentine’s day as they wine and dine their partners. But that does not mean that monogamy is not structuring our Valentine’s day thoughts. For monogamy as a socio-cultural technology does not just order our family commitments or finances, it also orders our emotional lives, sometimes as a useful, joyful constraint, one that for many can lead to, even actively produce, desired attachment and contentment. As a technology monogamy can thus also produce affective results, and serve emotional functions, positive or negative as we might judge them to be. In focusing on social reproduction heavily I am thus not denying the emotional and relational benefits monogamy produces for some (though these too can be part of social reproduction!) but simply acknowledging the social reality that this particular, still highly-popular and socially-privileged arrangement generates.

This may all sound like a strange lefty obsession, but it is not. Conservatives are very clear on the economic and social function of monogamy when they decry absent fathers or worry that welfare expansion will destroy families. Even supposedly liberal and feminist commentators sometimes insist that marriage is, while deeply imperfect, needed for precisely this reason. It’s common as an analysis across the political spectrum. It just doesn’t sound great on a Hallmark card.

Why, then, are many no longer doing monogamy quite so much, or at least abandoning it more openly? Commentators like Harper and Kearney acknowledge the role of class in their worried writings about family structure, but they do not conceptualise the relationship as directly and bluntly as they might. Since they do not, please allow me, so that I may more clearly posit the reasons for these social changes: today, monogamy is less common, or more openly neglected, because it is now too "expensive" (e.g. no longer so advantageous) for poorer people and simultaneously unnecessary for the rich. This, more than anything else, explains the double strand of op-eds decrying the supposed relational decadence of the rich and the relational poverty of the poor.

Wealthy people now do not need monogamy to ensure their children are provided for. They have alternate “technologies” for this, the babysitters Harper refers to, but also lawyers, prenups, paternity tests, cleaners, daycares, elite schools and therapy. Harper suggests these enable non-monogamous behavior, which is true, but really it’s more than this: these relative luxuries replace monogamy and what it has traditionally provided in terms of an exchange of labour during social reproduction. Many wealthy people (and the relatively bourgeois people that remain amidst widening inequality) still do pair up to engage in high-intensity parenting and create new small wealthy people, but they no longer need to do this in a way that involves sexual or romantic monogamy or even its pretense.

Poorer people, meanwhile, face a different problem: statistically, due to massive and very gendered changes in the nature of the workforce, working class men (and the middle class precarious men who would never think of themselves as working class) are less educated than their female counterparts. They live less stable lives, and earn less than the corresponding women of their generation. Therefore the old monogamous exchange, where men offer financial resources and women provide sexual and social reproduction, no longer serves at least one if not both parties. As Kearney puts it, “The mothers who are not married are not married precisely because the men with whom they have fathered children would not meaningfully contribute positive resources to the raising of their children.” Kearney herself notes people still idealise marriage in American society in many ways, they just want to hold out for the “right” relationship—which often means the right exchange, whether or not that will ever become available.

For rich and poor alike then, and many in between, it is not that people are simply making different personal choices due to cultural norms. Rather the socio-cultural technology of monogamy or even relative monogamy no longer offers the benefits it once did. And notice the directionality of this problem, how the job market and gender roles precede the relationship issue: even if we could pair people up tomorrow, their social-economic positions would still mean the exchange would not function as well as it used to. The economic, gendered problems at play are largely separate from, and cannot be solved by, the technology of monogamy. (These are very big problems, in fact; the same factors are at work in phenomena like incels and a possible widening gender gap in political views, for example). So while enforcing monogamy and marriage as a social norm might have some shorter-term benefits for children (and that's a big maybe!), to rush back and reinforce monogamy and nuclear family is like trying to hold back the tide on some other very real problems that require rather different solutions.

I worry about the stream of writings that do not have this specific part of class analysis because of the history and bedfellows that hot takes on modern sexuality tend to accumulate, however unwittingly. For even if Harper and Kearney might not desire or foresee this, their pieces and many others, by focusing on a return to individual choices, cultural norms, and even personal annoying-ness, in some ways fit with the long history of worries about “decadence” amidst societal decline. Both are basically worried about a certain kind of apparently harmful and immoral social behaviour at a time of political and economic decline, which is what this history of “decadence” worries historically involves. Harper is concerned that the wealthy are engaged in a form of decadence that is peak individualism and narcissism, and Kearny is concerned decadence has manifested as a reduction in cultural norms about commitment of a particular form, especially for the less privileged. And in this way, their writings fit with the history of worries about decadence which more commonly revolves around queerness, gender, race, and migration. It is exactly these kinds of worries that are unfortunately on the rise in both Europe and the US, with a particularly strong ongoing backlash against trans people.

The problem with cultural fears about decadence (besides their frequent conservative and reactionary veins, which are of course deeply important!) is that these fears generally have the wrong object in the crosshairs, the symptoms but not the cause, the harmless and multifaceted as well as the harmful. Yes, it is concerning that we live in a highly individualistic culture, and that this has leaked into our obsession with our own needs at the cost of frequent relational breakdown. Yes, it is probably a symptom, in part, of a neoliberal economy. We should be concerned. But many other “symptoms” of societal woes are in themselves not the cause for worry. Images of decadence in previous eras often involved paintings of raucous Roman parties, with the clear implication that this sort of revelry is what precedes the fall of empires. But wine and parties do not cause the fall of empires (in this metaphor we must assume empires are good, somehow). Nor do naked partygoers. Wine, parties, and sex are not immoral on their own. What is immoral, bluntly, is the homeless person outside the front doors of the grand villa, and the extraction and creation of an underclass that lead to that. Or the treatment of the folks being conquered and quashed at the edges of the empire.

In other words, let’s be realistic about what’s really a problem and why. Non-monogamy is generally cringe not because multiple people are consensually involved, but rather because relatively privileged people have dumped their neuroses and misguided aspirations for a “free” or authentic life, as well as their endless therapeutic jargon, on the endeavour. Harper is right to note that there is a culture of “therapeautic libertarianism” at work in many of the endless self-help books about non-monogamy (this trend drives me nuts too.) I think, though, that we would be wise not to blur the argument here and see relationship styles themselves as luxuries, especially not in a pejorative sense. If non-monogamy is a form of decadence, it is a curious one in that it focuses on a good that can conceptually be had and shared by everyone, even those without babysitters, and because it is about relationships rather than material goods. Certainly the odious have made it odious, but to imagine that multiple relationships are intrinsically a luxury good, in the sense of either being unattainable or outrageous, is to miss what is or could be actually at stake in human relationships for poor and rich alike. We should take seriously the human suffering involved in the way neither steady commitment to one nor happy thriving with many seem entirely possible for so many people today (notably, many fewer people practice non-monogamy than say they would like to!). Enforcing any one model of personal happiness will not, however, solve our larger economic and social problems.

Similarly, single parenthood is bad not for intrinsic sexual-moral reasons but because of the crushing burden placed on single parents by neoliberal working hours and atomised home lives. It is very worrying indeed that the Fordist model of the nuclear family, where one person can support several others comfortably, has become unreachable for nearly everyone—but it is worrying because we should have high wages and free time with our children, in whatever configuration they are raised.

These problems do not require and ultimately cannot be solved by monogamy. (Kearney in particular explicitly thinks we should encourage a return to the nuclear family form via cultural pressure, for example.) To pressure people to rely on what is essentially an outdated technology in a novel historical moment is to miss the real challenge of seeking better solutions to the problems of social-reproduction. Instead, resources for children can be found and distributed other ways. Indeed, they will have to be, in all likelihood, unless the trends around gender, education, and earning potential are all reversed.

Is consensual non-monogamy really more common now? Some statisticians think so, but in truth, we can’t really know, because measurement is so hard. People who answer surveys often have wildly different definitions. More than this, so much of consensual non-monogamy has been secret. My co-author Bri Watson and I wrote an academic piece on this a while back, combing the letters of famous historical non-monogamous people (their letters get saved). Most were somewhat closeted. Some kept the secret even from their own children; I still think frequently of the British aristocratic writer Vita Sackville-West getting outed to her children by her own mother.6 Even the decadent wealthy polyamorourists of the early 1900s kept the matter from their children.

What we do know, though, is that then as now the practice varied widely in its nature; it can certainly be a vehicle for men to keep mistresses or irritating people to pursue individualist pleasure, but so too can it be a collaborative experiment, a form of community, and a re-arrangement of family. The people documented in our study kept households together, raised each other’s children, stayed together for lifetimes, aided each other’s work and stayed by each other during war, illness, death and grief. Much of this is the sort of relationship style I get to experience daily, too, living with my partners and my cats as I do, and I am both grateful and hardly special for it. There are lots of people like me. We are, of course, also doing a social reproduction, making the world over and over again, just slightly differently. We are generally using a different relationship style and thus socio-cultural technology in a way that is responsive to the precarity of neoliberalism—not liberated from it, because we have of course not escaped material and historical trends. But though we cannot escape these trends we can counter some of their isolating or libertarian effects, and so live in a less individualist, more communal and fairly committed way.

All of this to say: social technologies shape our possibilities, but only so far; once we have access to their varied affordances we build relationships case by case. Just as the internet enables both 4-chan and wikipedia, non-monogamy enables both Sam Bankman-Fried’s hyper-libertarian, cuthroat “Chinese harem” and a large number of content, respectful relationships and families. (The former libertarian way does seem to get better press, though, and this is indeed a problem, as Harper points out.) This is why, rather than see non-monogamy primarily as a symptom of neoliberalism or a cause for panic and a return to old norms, we should think about what monogamy and non-monogamy each enable for us and how to use their varied possibilities more wisely.

And so I suspect we should not ask if non-monogamy is annoying, or if it is a luxury good, or if it is hurting the children. Instead we should return to the problem of better forms of social reproduction and ask: if two parents good, perhaps three parents better? Perhaps motherhood communes better? Perhaps parenting with friends better? We can’t really know yet—but we could reorganise our social practices and legal norms and find out, as some people are already doing. As for the cringey-ness of the rich and promiscuous, well, we might be stuck with that…for now.

Although monogamy is usually employed in ways that keep individuals within their assigned class there are, occasionally, interesting exceptions to this rule. In previous generations, men frequently married hot but poor women, if we can put it bluntly - their secretaries for example - and that lead to some measurable social mobility. Now that women too can be highly educated and work in fancy jobs, we’re seeing what economists call “assortative mating”, which has meaningfully contributed to wealth inequality, as both men and women now generally choose their heterosexual partners to roughly match their wealth and education levels.

One reason I like to think about monogamy as a socio-cultural technology is that it helps one get away from the long and boring debates about whether monogamy or non-monogamy are “better,” as if this could ever have a single answer for all people across time.

Something something Max Weber.

Here I use the conventional trappings of gender for the perhaps obvious reason that these are deeply implicated in this marriage form.

Is this exchange generally conducted “fairly”? Perhaps not, but that’s another matter.

Her partner Virginia Woolf heard of this and said, ‘The old woman ought to be shot.’

Love this! I’m Harrison, an ex fine dining line cook. My stack "The Secret Ingredient" adapts hit restaurant recipes (mostly NYC and L.A.) for easy home cooking.

check us out:

https://thesecretingredient.substack.com

Isn't polyamory a socio-cultural technology then?