[This piece was written as response to a showing of the film Join or Die at the Kairos Club and presented on September 4th, 2024.].

The film should come with a trigger warning for Hilary Clinton, for those of us who find her appearance painful in any number of ways. She appears early in this film, in a sudden jump cut. (Pete Buttigeg does too.)

A shock for the viewer, perhaps, but not truly surprising. For when the political scientist Robert Putnam first published his famous article, “Bowling Alone”, in 1995, it immediately launched him not only onto the pages of People Magazine but into the outstretched arms of America’s elite politicians and government. Then-president Bill Clinton invited him to the White House to discuss his works’ central thesis: that Americans were forming fewer and fewer social ties and and that this decline in “social capital” and civic life had harmful effects in a number of areas, from voting rates to neighbourly behaviour to the effectiveness of local government.

Putnam’s relationship with the American government didn’t stop with his 90’s-era trip to the White House. As one sees in the film, Putnam went on to join a cross-party group, the “Saguaro Seminar,” aimed at solving the problems of declining social capital. Then-community-organiser Barack Obama was also a member. (The group never found any grand solutions). Later, President Obama awarded Putnam the National Humanities medal.

Putnam is one of the most cited political scientists on political science courses; his theories were some of the first I ever read as an undergraduate. And this film, no doubt, will now become a part of so many intro political science and sociology courses, introducing students not only to the idea of social capital but to Putnam’s moral cry: that everyone should join a club, and build social capital that way, via knitting clubs and bowling clubs and more.

Besides Hillary Clinton’s appearance, that is the curious bit about the film: that it involves a moral cry, an individual one. Putnam is 84 now, and what one notices about him right away (after the striking chinstrap beard) is that he is extremely emotional about his life’s work, and sees it as a moral calling. He cries multiple times in the film, especially about John F. Kennedy. (The first audience I showed this to, a bunch of European sociologists and entrepreneurs, were quietly appalled by these displays of emotion).

Putnam isn’t (mostly) asking for any change in government policy; he’s not even asking for political scientists to conceptualise the issue differently, since his framework for this problem is now the standard way of seeing things. No, he’s mostly asking for individual people to take action and join largely apolitical clubs across America: Join or Die.

This emphasis on individual-call-to action is rather curious as a choice for a social scientist. After all, if I may include myself in the profession, even in only the broadest possible sense, I think it’s fair to say that we’re mostly asked to look at things in structural terms: as a matter of institutions and large-scale processes. Sometimes, we get to look at them in terms of culture. But it’s very rare that things are framed as a matter of an individual’s morals, not only because it’s not clear what is left to name as morals after we have accounted for structures, economics, and culture, but also because sociologists and political scientists are generally meant to influence governments and policy-makers, not individuals. We are, bluntly put, generally analysts for those in power, not personal gurus or priests for the masses. Accordingly, other political scientists and sociologists who consider the question of social capital tend to do so in structural terms, trying to understand its relationship with inequality, or with “social infrastructure,” the spaces and even temporal moments that allow for people to begin to form meaningful long term connections with each other.

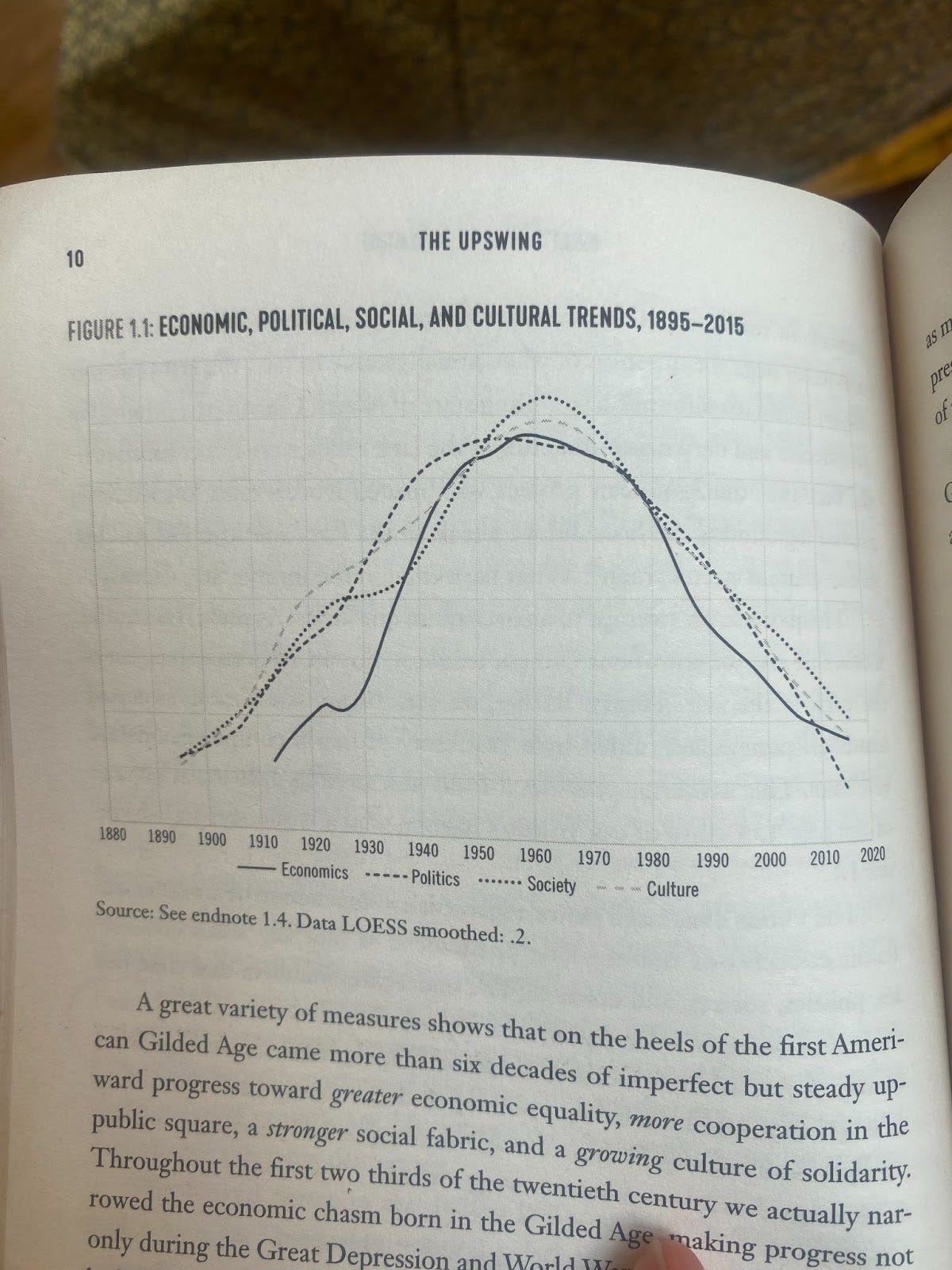

But Putnam has chosen a near-individual lens for much of the film. It’s especially striking because in his last book, The Upswing, written with the Shaylyn Romney Garrett, he argues that in the Gilded era America was, by nearly all metrics, an individualist or “I” society, that it then slowly over decades, leading up to the 60s and 70s, it became a far more community-oriented, equal, trusting “we society,” and then trends then reversed so that we are now once again at a low point in America’s history: America is currently at an extreme low point in at least four areas: inequality, political polarisation, a lack of social trust and cooperation, and more broadly, a high level of often-harmful individualism.

Asking individuals to join clubs, although a community-oriented request, is still in some ways an ironically individual approach to solving these enormous, complex social problems and interweaving trends.

If I were to allow myself to speculate, perhaps this latest film takes its rather individualistic approach to how things should change because Putnam has lost faith in the government to make a difference. After all, it has now been nearly 20 years since Putnam was invited to the White House and the problem he has made his life’s work has, if anything, gotten much worse. Consider this excerpt from the New York Times interview with Putnam about the movie:

Interviewer: I’m listening to you talk with this passion, I’m thinking about, in the documentary, you sitting at the table with President Clinton, and you must have felt at that moment as if your message was going to be received. You must have felt so hopeful at that point.

Putnam: Sure, and in fact, I felt even more that way about Barack Obama. I was incredibly hopeful about Barack Obama, not just because of who he was, but because I actually knew him well. Until he became president, he called me Bob and I called him Barack.

Interviewer: And yet, I hear you, and your passion is so great, and I’m moved by it, frankly. But here we are.

Putnam: Yeah. So, I don’t know. You shouldn’t think I’ve never asked myself that question. One way to put it is this: Twenty-five years ago, I essentially predicted everything that was going to happen….I’ve been working for most of my adult life to try to build a better, more productive, more equal, more connected community in America, and now I’m 83 and looking back, and it’s been a total failure. …But I am hopeful, because I can see how we could change it, and I’m doing my damnedest, including right this moment, to try to change the course of history. I’m sorry, that’s very self-important and I apologize for that, but I’m telling you honestly how I feel. I don’t mean to sound cynical, it’s just, What can I do? I tried my damnedest to sketch a way forward, but I’ve not been persuasive enough.

There’s so much we could “unpack” in this moment of the interview: Putnams’ affection for the elite politicians, his hopefulness, his hopelessness, his sense that his task is persuasion, his sense that his task was persuading these people in particular (instead of say, working at a grassroots level or with people who do so.)

But rather than dig at him for cavorting with elites (wouldn’t many of us, if we wanted policy solutions?) I think it’s more helpful to consider that Putnam realistically shouldn’t be quite so surprised that governments haven’t done more to restore social capital. Despite the many positive benefits of social capital (trust between neighbors, political tolerance, even longer and happier lives) social capital has its downsides for those in power. It creates an alternative locus for political life, civil society. As Putnam notes plenty in his own book on the matter, Making Democracy Work, social capital increases people’s demands on governments for accountability, which many of those in government, er, do not actually want. More than this, allowing people to gather and discuss politics at length often means they decide they want another sort of politics altogether.

Indeed, governments have long been skeptical of, and even actively hostile too, some of the “social infrastructure” that tends to allow civic ties to flourish. When the Chartists in the United Kingdom used public parks to hold giant assemblies, rallying to create civil rights and the vote for the ordinary British person, the government not only policed their gatherings extremely heavily (recruiting a whole civilian brigade!) but also re-landscaped the entire commons to make it nearly impossible to hold gatherings there in the future, which is why Kennington Common is now Kennington Park.

The history of coffee shops is similarly filled with government shutdowns. In the early coffee shops of the Middle East, rulers repeatedly shut the coffee shops. The ruler of Meca, (Kha’ir Bega), not only banned coffee-shops in 1511, but apparently held a trial with a basket of coffee on one side and a prosecutor on the other.1 The silent basket of coffee was officially accused of making people lose focus on Allah, but notably coffee shops had also become the place to go if you were dissatisfied with the rule of, well, Kha’ir Bega, and it was convenient to him to have them gone. In 1633, Sultan Murad IV of the Ottoman Empire made drinking coffee itself a capital offense after members of his family were murdered by soldiers who had previously frequented coffee-houses.2 The same complex relationship between power and civic life occurred when coffee became part of everyday life in Europe. In 1675, King Charles and his ministers attempted to shut down the coffeeshops that had begun to spring up around the country, fearful that they would lead to attempts to overthrow the throne (and indeed, some of them probably would have).3 Coffee shops were not only powerful because they connected people but because they created a new set of social norms and behaviours, so that citizens learned to relate in a particular, civil-yet-sometimes-argumentative way that had not previously flourished in other gathering spaces like church. These coffee-shop changes in behaviour were striking enough that some worried they would turn men idle, gossipy and sexual impotent. Indeed, there was a broader hysteria that men might, through coffee shops, become generally effeminate in their mannerisms and behaviour. (This begs the rather interesting question of whether discursive civic virtues are, in some sense, “feminine”, as in tied to the virtues most commonly attributed to women. Anyone who has had to sit through a seminar dominated by men might agree). In any case, political rulers continued to regularly spy on, ban, and police coffee houses and other public spaces precisely because they knew they were places of political unrest. In Germany, Frederick the Great attempted to ban coffee in 1777. The history goes on and on (sadly I can’t cover the unbelievable history of coffee-shops here, but I strongly recommend it as a Wikipedia rabbit-hole).

The point, of course, is this: social capital is sometimes good for society but it is also costly to those in power. This is not a uniformly progressive fact, either. Some research shows that Trump supporters actually have relatively high levels of social capital in their areas and have effectively used that to mobilise. Some also theorise that groups like the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt are successful compared to competing groups precisely because they build and control the social infrastructure (Mosques, schools, etc) on which people’s social ties depend.

It should not surprise us that politicians want to pay lip service to the benefits of social capital, which are many, but it should also not surprise us that they want, at most, a version of social capital is controlled by them directly, or that feels tame and relatively apolitical. Politicians might not mind a rise in bowling clubs, but they sure do hate an encampment (think not only of those today but also of what happened to all of Occupy). Indeed, many politicians do not even favour walkable cities because these can lead to political mobilisation. In Chicago and other cities in the last century; entire tramlines and walkable street layouts were destroyed in part to prevent people, especially Black people, from easily visiting each other and forming potentially political social lives.4

It is not obvious that those who run America today would want to encourage people to build up their social capital, although if they did want to encourage this, inviting them to “join a club” is perhaps the least radical and least politically “dangerous” way they could do this. Those in power want social capital, but the tame version. They might befriend Putnam but they’ll rarely create massive changes.

This explains not only why Hilary Clinton is in this film but also why government initiatives about “loneliness” are so frequently couched in careful, apolitical language. The Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy, who appears in this film, has announced that America is facing an “epidemic of loneliness and isolation”. He advocates for what is very nearly a sort of anti-loneliness “public-private-partnerships”: “[i]t will take all of us – individuals and families, schools and workplaces, health care and public health systems, technology companies, governments, faith organizations, and communities – working together to destigmatize loneliness and change our cultural and policy response to it.”) Although the policy document he has put out does start with a discussion of social infrastructure, this sort of framing of the issue often elides the material underpinnings of the problem, the political dimensions of gathering, the economic causes of our profound disconnection from one another.

Social capital isn’t just a threat to governmental power structures. Creating it involves trade-offs with other areas of human life, especially with paid work. Time spent cultivating the complex, interesting, important bonds of civic life requires people to give their time and energy to forging these social bonds rather than engaging in other, individual pursuits, including and perhaps especially work. (But think also: tending alone to your nuclear family to make sure your kids get into the best schools, working extra on your side-hustle, self-improving to find your soulmate, etc). Sitting around discussing politics (or for that matter, literature or the latest netflix show even) is, quite simply, “unproductive” for our current economy and less individualistic than most of our current cultural trends.

Isolated people make good workers, on the whole; and don’t cause a lot of trouble. Connected people are frequently the opposite. Governments are now facing a series of public health crises and appear to wish to address their roots in people’s isolation, but that does not make social capital any less tricky for them to navigate.

That contradiction lies at the heart of Putnam’s approach to his work. It forces us to ask: what if it is not in the interests of the elites to solve the problem Putnam has lovingly laid at their feet, and now at ours?

All of which brings us round to two things that are only barely discussed in this film, and also only somewhat discussed in Putnam’s last book, The Upswing. Namely: 1) what is causing this profound depletion of social capital? And 2) what should we all do about it, besides join a club?

Let’s start with the first. Putnam is right to note that, like nearly all great social science questions, the matter of declining social capital is complex and “overdetermined,” with many different variables all pushing in the same direction. Everything from the decline of religion, the rise of women working outside the home, to inequality and the internet have likely had some effect.

But, notably, not all of the factors are influenceable. We should not try to influence women to go back to the home, and good luck to anyone trying to put the internet back into its box. Despite this, Putnam and his co-author mostly spend time discussing which variables are not at play or are not absolutely primary players This is a shame, for some of the latter variables are in fact precisely the dials that policy-makers have access to. What’s most striking is Putnam’s dismissal of material, economic causes for a decline in social capital. He does this largely by noting that inequality increased only after social capital had begun to decline, and only after certain kinds of polarisation had taken place, before other forms of polarisation. He construes all these facts and graphs (and he loves graphs!) to mean: if inequality follows from polarisation, then it cannot be the moving cause of the decline in social capital, and we must look elsewhere for further research.

This might be a little hasty. Let’s try to look at things another way.

Note, as Putnam himself notes in his book, that most polarisation in America comes from the right (that is, it’s not that the left becomes more left-wing when polarisation happens, it’s that the right becomes more right-wing.)5 Polarisation also tends to come from above: as Putnam notes, elites’ stated views become more polarised first and the rest of us follow.6 So when polarisation happens, it’s right-wing politicians that tend to move first, and the rest of us polarise after.

Imagine, then, interpreting the same facts this way: those who own capital want to get ahead with their new business plans. Perhaps, after a couple of decades of postwar prosperity, they are looking for new ways to secure profits, before their profit margins narrow too much via competition, so that they can take advantage of new opportunities present in globalisation while avoiding any negative aspects thereof. They might first influence the most elite politicians to deregulate or reshape the economy.7 As time goes on, inequality will increase, and the less important politicians will also polarise to match the increasingly polarised rhetoric of the elite politicians.

Here, measurable inequality follows other measurable variables like polarisation or cultural mores for that mater, but it would be foolish to say that economics was not a or even the major causal factor. We can see how this works in plenty of other areas of life. I might purchase a car only after my friends and I realise we can get better jobs further away from our houses, but that does not mean my purchase isn’t driven by economic pressures.

I am not claiming this is definitely what happened in America (and apologies to my non-American audience for focusing so closely there so as to address Putnam’s work directly). Someone more versed in the statistical analysis of the economy will have to take a crack at my theory and see if any of it holds water. (Even if I am right, I will be fractionally so, for many other factors are surely at play). My point is more that we should not take the analysis provided in the film, or in the book, as definitive, and should in fact question how it handles these difficult causal questions. Putnam dismisses the economic drivers for the loss of social capital too quickly (as well as the work of a number of Marxists, who he dismisses as, well, Marxists) because he only frames economics as primarily a matter of measurable inequality, avoiding any discussion of certain kinds of class interests, elites influencing each other, power, or ideology. (And the individualism he wants to curb is indeed ideological).

All this matters because it would, in short, be a shame if this film, which is likely to become a mainstay on curricula everywhere, became the definitive way that young American undergraduates came to grapple with the still-very-important question of social capital and how we can rebuild it. Putnam repeatedly notes we need not just moral but structural solutions, but then he provides hardly any of the latter. In his book, he instead focuses many pages on the biographies of four apparently extraordinary individuals who he sees as sort of moral pioneers, selflessly devoting their lives to various causes. At one point the book declares, “as all of these stories illustrate, the Progressive movement was, first and foremost, a moral awakening.”8 Policy suggestions are not made. Suggestions for social movements to act on are not extended. The role of those in power is not questioned (not least because some of them appear in the film!) And so on.

The problem, by the way, is not that there isn’t any moral element involved. Perhaps it is indeed our individual moral duty, at some level, to found and join a club, to take up the reins of civic action. No, the problem is that there are so many other aspects of this problem, things that need to be addressed collectively, materially. The analysis is incomplete, and important solutions that could actually be implemented are left unexplored.

So, let me attempt to pick up what was dropped, however briefly. We probably need to do much more than join a club if we want to exit the rather lonely, alienating, individualist world in which we currently reside, or even “save democracy”, as Putnam would put it. We need to build the economic, physical, material infrastructure on which clubs tend to depend, which has been depleted in the last 50 years due to neoliberal economic policies, a decline in religion, the destruction of unions by changes in the economy but also vicious legal action. We need to reclaim public spaces from privatisation. We will probably need to root out government suppression of our groups and spaces too, if history is anything to go by. We need to push back on the many forces that actively benefit from us working long hours and having few spaces to go to to meet and socialise with new people. We can, again, do this in part by unionising (both at work and through consumer unions, e.g. food co-ops).

We also will need to build spaces outside the control over the government, including explicitly political ones, like the one we’re in tonight. Some political scientists suggest that, while the internet is not a good space for building social capital, “alloys”, that is groups that exist online but work to bring people together in real life, can have some positive effects. We need to revisit the relationship between social capital and inequality (and particularly the economic pressure on politicians) immediately if we want to achieve some of these things. Only in doing so can we address not only our own personal alienation and isolation but some of the root causes of everyone’s increasing alienation, which is a more profound problem than “loneliness”.

As for us social scientists, we shouldn’t show this film uncritically. There’s more to tell those who watch it, especially young students. The social fabric doesn’t just decay because of some lapse in our moral fiber. As Jane MacAlevey (RIP) notes briefly in one of the few political moments in the film, there are people out in the world who work to take that social fabric apart. To understand the problem we’re facing, and to address it, we have to undo their work, and often take them on directly. And we have to believe not just in clubs and the power of graphs but in matters of power and ideology. Clinton and Obama are unlikely to help us.

This may all sound rather harsh towards an older and eminent scholar. But in our field, as in so many, you know you’ve made it when people spend the rest of their lives trying to prove you wrong. Putnam is profoundly, movingly right about this issue existing and its dire consequences. He just hasn’t got the political analysis we need to actually make an inroads into solving it. Let’s develop that together - in clubs, yes, but in so many other ways as well.

See The Upswing, page 86. Political scientist Nolan McCarthy is there notably quoted: “during the period of increased polarization, the main driver has been the increasing conservatism of the Republican party.”

See The Upswing, page 92. (That is probably also when you could measure shifts in other economic variables related to social capital, like the defunding of public spaces and other forms of social infrastructure. But those remain unmeasured in the film, and in his recent book).

As any person who has lived in DC can attest, the effects of capitalism are not always felt first as income inequality. They may first be felt as the political influence of capital-owners on politicians. (I grew up amid just this sort of lobbying)

327.

Do you think a four day work week would be helpful in getting us all to socially cohere?

Thanks, Sarah. This was a great read in my coffee shop of one this morning. That governments don't want uncontrolled person to person assembly is pretty obvious; governments want fealty. You've got me thinking about the government supported social science field of psychology. Particularly behavioural psychology. Governments and businesses both want "normal" people. They want the threat of "abnormal" to be very real. The outcry about an epidemic of loneliness for what might often better be named restive alienation is a case in point. I'll take that with me as I go about my round of coffee shops.