Excerpt: Cognitive Dissonance

What is it, outside the common usages, and why might it be closely tied to our political consciousness?

My PhD is due in two weeks. While I’m deep in revisions, here's a small piece of it...with a bit about an alien cult, a video of a deceptive study in a lab, research that shows how people might become attached to the idea of the American Dream, and more. It’s a little more academic in language than I would usually post on here, but it may of be interesting all the same.

What is Cognitive Dissonance?

Cognitive dissonance is a psychological phenomenon first described by the psychologist Leon Festinger, his colleague Henry W. Riecken Jr., and his student Stanley Schacter. The three experimental psychologists published a book entitled When Prophecy Fails in 1956. In this book Festinger et al describe how they had uncovered the psychological phenomenon while infiltrating a cult, the Seekers, who believed that aliens would arrive on a particular day and bring about the end of the world. When these aliens did not appear, the cult members experienced acute distress, sitting in stunned silence, crying, and trying to come up with explanations, until they “received” a new message through their leader, which read: “The little group, sitting all night long, has spread so much goodness that the God of the Universe spared the Earth from destruction.” At this point, although some members of the cult remained distressed and left, the majority soon agreed on a new narrative, in which all their devotion to the cult had spared human beings from destruction. In this way they doubled down on their existing beliefs and came to believe even more deeply in the aliens, despite having just been faced with information that appeared to contradict said beliefs. Festinger theorised that members of this cult sought to resolve the apparent dissonance between their extreme behaviours (leaving jobs and even marriages to await the end of the world) and their subsequent cognitions (that aliens had not arrived) by establishing a new narrative and reinforcing the new narrative with even more intense levels of action and devotion. Subsequently cult members invested further in these beliefs by starting to proselytise for the first time, since the idea of “saving” others had now become an established part of the cult’s narrative.

A news item about the cult that was first studied by dissonance theorists

Festinger et al described cognitive dissonance as “a motivating factor in its own right” for human behaviour, defining it as the discomfort subjects face when they recognise a contradiction between two or more cognitions or behaviours. Dissonance, or very specifically the existence of “dissonance discomfort” was theorised from this point onwards as an uncomfortable tension that “has drive-like properties and must be reduced.” As the discomfort created by the gap between two or more thoughts or behaviours increases, subjects become highly motivated to reduce dissonance discomfort quickly, with efforts proportional to the amount of discomfort. Subjects might do this through a combination of changing their actions, changing their opinions, or finding a way to make contradictory cognitions no longer appear contradictory – just as the group in the original study had changed their beliefs to explain that it was no longer the end of the world, yet aliens still existed. These behaviours are the measurable, and often seemingly irrational, evidence for cognitive dissonance.

Further laboratory research by Festinger and other psychologists demonstrated the same type of cognitive dissonance in less extraordinary situations. In 1956, Festinger, Riecken, and Schacter conducted a lab-based study in which participants were asked to complete an extremely boring task involving moving wooden pegs and spools of thread. Participants were then debriefed and told that they were in the control condition of a study, where they had been asked to do this task without any pre-existing expectations. (This was, however, a ruse. The most important part of the experiment was yet to begin) In the experimental condition, the experimenter explained, the other half of the test subjects would be told ahead of time that the task would be fun, and the experiment was to test how much these expectations shaped students’ perception of the task. This entire explanation was, however, a lie, designed to set up the next part of the real experiment. The researcher conducting the study would then explain that the next student who was serving as a test subject would be in the experimental condition, and that a confederate of the experimenter was meant to go out shortly to the waiting-room to tell this next student that they had just done the experiment and that it was a lot of fun. Annoyingly (the experimenter would then muse aloud) [the confederate] had not shown up today. In fact–the experimenter would ask—would the student play the part of a confederate, for pay, and go tell the next student how fun the experiment had been? Although they were not required to do so to secure class credits, most participants nevertheless chose to lie to the next test participant to assist the experimenter. Participants were then compensated either a small amount of pay (1 dollar) or a larger amount of pay (20 dollars) for serving as a confederate, before finally (privately) completing a survey on how enjoyable the task had been. Notably, it is at this point that the effects of dissonance became measurable: those who had been paid a small amount to be a confederate rated the original (boring) task as far more enjoyable than those paid a large amount of money to lie about the same task.

Festinger and his colleagues theorised that this difference in how participants rated the task demonstrates the effects of cognitive dissonance. Without dissonance, in theory, subjects should perhaps have not changed their real views on how interesting the experiment was at all, regardless of whether they had chosen to lie to someone else about it or how much they had been compensated for that lie. Or perhaps those paid more would somehow have associated the reward, pay, positively with the task itself and those paid more would retroactively consider the task interesting. But in fact the opposite occurred and those rewarded least for lying came to believe their own lies the most. This, Festinger and his colleagues suggested, was because the contradiction between lying and not being paid well for it was painful—the subjects knew that the task was boring, and had not been paid well to lie, but had done so anyway. That contradiction was uncomfortable, and, the psychologists suggested, to resolve the discomfort, subjects unconsciously revised their beliefs, and came to think the task interesting, as this was the easiest way to resolve the discomfort. After all, if the task were really enjoyable, they could consider themselves to not have deceived anyone. (In contrast, students who had been paid a good deal of money to lie to the next participant in the study did not experience much dissonance, as they could explain their behaviour in terms of the high reward.)

You can watch clips of this study above!

Yet another, somewhat similar method of arousing cognitive dissonance is the induced-compliance paradigm (originally termed the forced-compliance paradigm). Festinger et al’s study involving participants twisting spools of thread, then reporting that the activity was in fact interesting, is an example of an induced-compliance paradigm. Recall that dissonance was aroused by the conflicting cognitions of “this activity was boring” and “I told that person the activity was interesting, despite the fact that I was paid poorly to do so.” Dissonance was reduced in this case by participants revising the first cognition and coming to believe “this activity was interesting.” (Subjects who were paid highly to tell others the activity was interesting did not revise their views, as their dissonance was reduced by the fact that they were paid well to lie, which is compatible with the activity being boring). The ability to choose freely whether to engage in the task appears to be key to triggering the dissonance, although there are multiple possible explanations for this…

Cognitive dissonance theory is considered an important and in some ways unexpected finding not only because it results in peculiar behaviours but because it demonstrates a way (or several ways) in which humans do not operate according to conventional, classical economic or utilitarian ideas of rationality, where individuals are expected to calculate what is to their material benefit and act accordingly. For example, in several of the aforementioned paradigms, subjects work harder or change views further when doing so is associated with less of a material reward. The theory suggests subjects are sometimes more motivated by making meaning out of their actions than receiving external rewards. Because of this, the theory challenged the existing and popular behaviourist strand of thought within social psychology. Behaviourism is a psychological theory premised on the idea that learning happens through reinforcement, and that animals, including humans, will do more of what brings rewards and less of what causes punishments or unwanted outcomes. Notably, many ideas in behaviourism are very similar to the ideas driving classical capitalist economics. In classical economic models, human beings are considered to largely be “rational actors” pursuing rewards (e.g. lower prices, higher salaries, or better commodities) in line with their individual interests and this in turn is held to explain why markets lead to an efficient distribution of resources. In addition to the way dissonance theory suggests subjects may be more motivated by money and external rewards, dissonance theory also posed a methodological challenge to behaviourist models because it required a more complex account of the internal life of the subject, with multistep internal processes, even unconscious processes. In contrast, behaviourist psychologists, as the term suggests, tended to insist on relying solely on measurable behaviours as their source of data; they would simply look at the relationship between the rewards or punishment offered and the behaviour that resulted, insisting that to consider anything else was mere guesswork. This behaviourist methodological commitment had developed in part as a reaction to earlier, Freudian-inspired psychological research focused on inner states of mind that were difficult to measure. Cognitive dissonance opened the door once again to complex, meaning-focused explanations for human behaviour, to a rejection of a purely economic-rational psychology, and to a place for the unconscious in empirical psychology.

Two common and apparently irrational responses tend to result from the discomfort of dissonance—rationalisation and confirmation bias Rationalisation generally entails giving a reason for a decision that was not in fact arrived at because of that reason. For example, a person who chooses to smoke because they are addicted or simply because they find it pleasurable may rationalise that it is “good” for them because it makes them less hungry and helps them maintain or lose weight, but this is not in fact why they smoke and smoking may of course make them unhealthier overall. Confirmation bias is often used in psychology to refer very broadly to patterns of reason where subjects selectively accept and place more emphasis on ideas and information that confirm their existing views (and dismiss those that do not). A smoker may, for example, find reasons to discredit studies suggesting smoking is bad for them or point to the long lives of a few celebrity smokers while dismissing deaths of younger smokers as occurring for other reasons. These two approaches-in short, generating new ideas and choosing which ideas to accept to arrive at the conclusion that iseasier or more comfortable-are classic examples of how subjects resolve cognitive dissonance in seemingly irrational ways. It is these two mechanisms, rationalisations and confirmation bias, that often create what we might point to as “false consciousness” or a holding tight to harmful and innaccurate political beliefs, ones that limit one’s own agency. Rationalisations and choosing to only believe information from some sources allow subjects to continue to hold on to harmful and oppressive beliefs. Moreover, because these phenomena happen unconsciously, and appear to happen with relative regularity in any given study, it is likely that they may not be eradicable, at least not fully. This in turn means accounting for them becomes crucial. These behaviours often allow people to come to hold beliefs that are full of contradictions and may be oppressive, and help them to continue to hold these beliefs even when presented with good reasons to abandon them.

…

Some Evidence Dissonance is Especially Common Around Political Issues

Dissonance is particularly likely to be triggered by explicitly political issues. (I am here defining “politics” and the term “political” broadly, as having to do with social and collective relations of power, those of the sort that can be influenced by group interventions.) One reason dissonance is highly likely highly to arise and be a relevant aspect of analysis in political situations, e.g. when people consider their relationship to structures of power and domination, is because it is a phenomenon triggered by subjects’ sense of self, their sense of agency, their sense of their future action-possibilities, or some combination of these three.1 In many cases, political issues involve at least one or two if not all three of these possible dissonance triggers, whether or not those experiencing the dissonance recognise their concerns as political. Another way of thinking about this is that dissonance literature is closely related to how subjects understand their own agency (defined in the psychological literature in terms of apparent free choices and their perceived negative and positive effects, although it can of course be defined differently for critical theorists). Cognitive dissonance is therefore a ripe area for further study of how people’s political attitudes are formed. This theoretical point is interesting on its own, but more so for being closely tied empirical evidence—along both sociological and psychological grounds - that dissonance may be at work in certain kinds of false consciousness, as well as the way that dissonance may be most triggered by political issues. An example of this first phenomenon—dissonance’s involvement with certain aspects of false consciousness—is the work of John T. Jost, a social psychologist unusual for his interest in the question of false consciousness. Alongside fellow researchers, Jost has developed his own theory about why the oppressed often view the systems they live in as fair, “system justification theory”:

According to system justification theory, people are motivated to preserve the belief that existing social arrangements are fair, legitimate, justifiable, and necessary. The strongest form of this hypothesis, which draws on the logic of cognitive dissonance theory, holds that people who are most disadvantaged by the status quo would have the greatest psychological need to reduce ideological dissonance and would therefore be most likely to support, defend, and justify existing social systems, authorities, and outcomes.

Jost notes that there are, even at a psychological level, numerous reasons why oppressed subjects will reason in this way: “Some reasons pertain to information processing factors, such as cognitive consistency and cognitive conservatism, attributional simplicity, uncertainty reduction, and epistemic needs for structure and closure…Other reasons are more overtly motivational, including the fear of equality, illusion of control, and the belief in a just world…” While many of these psychological factors are common to all groups, including the elites in society; Jost argues that dissonance theory in particular is required to explain why those who a social system least benefits are in many cases most committed to justifying it. In several papers, Jost has argued in several papers that the sociological data about the views of the oppressed in The United States regarding the fairness of its economic system can be meaningfully interpreted as a rationalsation response to uncomfortable dissonance about the contradiction between their lived conditions and the ideology of the American Dream. In one study, for example Jost and his co-authors report:

“… low income Latinos were more likely to trust in U.S. government officials and to believe that the government is run for the benefit of all than were high income Latinos… poor and Southern African Americans were more likely to subscribe to meritocratic ideologies than were African Americans who were more affluent and from the North, (d) low income respondents and African Americans were more likely than others to believe that economic inequality is legitimate and necessary…Taken together, these findings provide support for the dissonance-based argument that people who suffer the most from a given state of affairs are paradoxically the least likely to question, challenge, reject, or change it.”

The cognitive dissonance involved may be created by the dissonance between the evidence from the world, on the one hand, of relative injustice and oppression and poor outcomes for individuals in the same position, and, on the other hand, a cultural and ideological belief that with hard work anything is possible or that they are in control of their own destiny personally. Many subjects appear to resolve this uncomfortable cognitive dissonance by doubling down on the idea that the system is fair after all. This appears consistently at a large scale and across a variety of political and social issues. Moreover, since resolving dissonance in this way preserves a (perhaps false) sense of agency and action-possibilities, this theory aligns with research that emphasises the importance of these as triggers for dissonance.

…

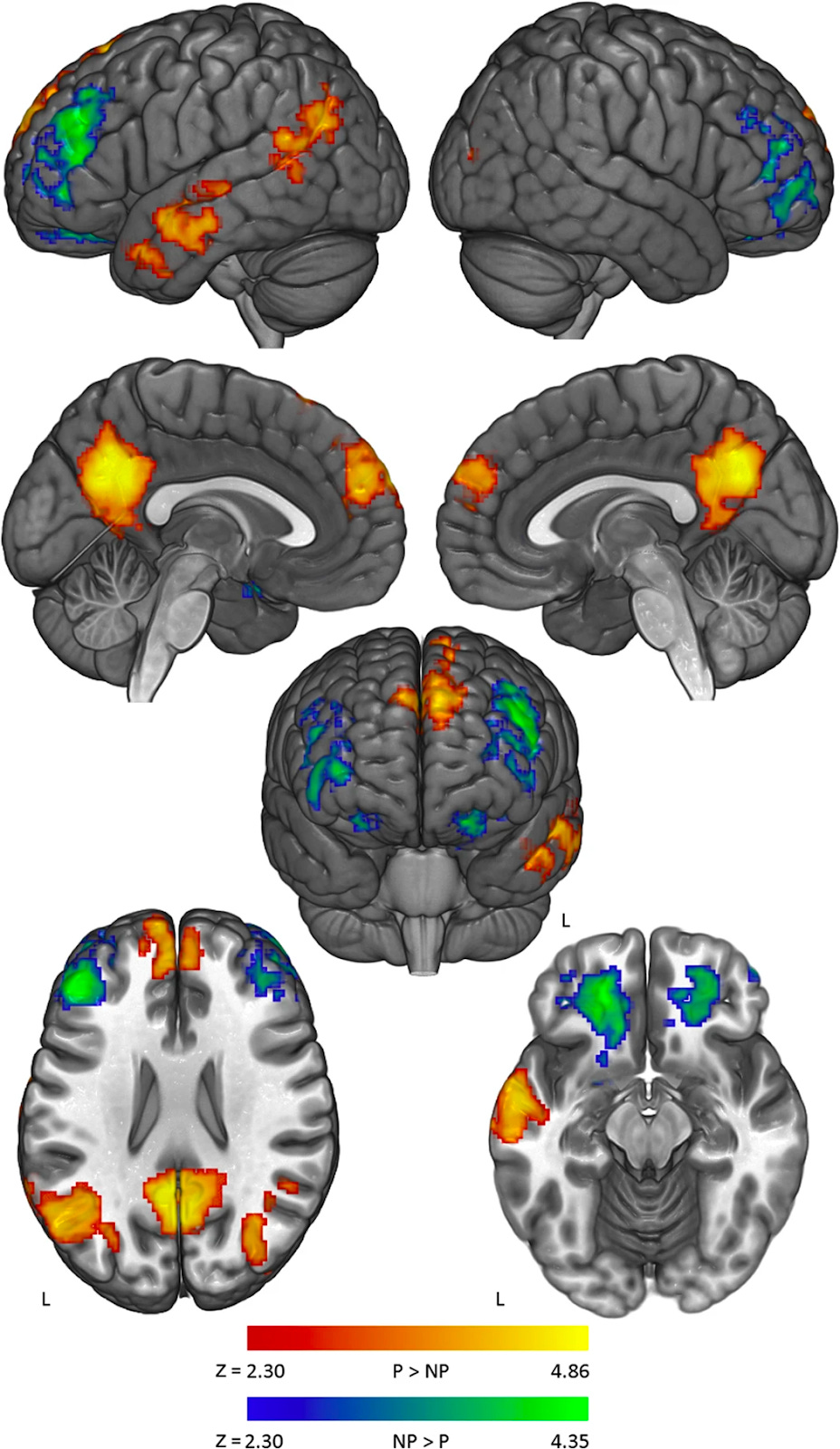

One especially illustrative and interesting lab-based study that touches on the way that political issues are especially likely to trigger dissonance is a 2016 study Jonas T. Kaplan, Sarah I. Gimbel and Sam Harris.2 The researchers put American self-identified liberals in an MRI machine and exposed them to evidence that contradicted a number of their views – half of which were political, half of which were equally strongly held non-political views (e.g. about historical facts). With probability values of less than .001 (strong statistical significance) they found that subjects’ political views were much less likely to change as a result of exposure to contradictory evidence than were other, equally strongly held beliefs. Moreover, changes to political views were far less likely to “stick” in a follow-up survey completed several weeks after the MRI test – in fact, participants returned to having almost identical political beliefs at the same strength, while the strength of their non-political beliefs was somewhat altered by evidence against it even after a few weeks. The extreme ends of the study’s results (as shown on the graph below) are telling.

On the far right hand side of the graph are the topics where subjects were most likely to change their views. Subjects had a relatively easy time responding to evidence that Thomas Edison did not invent the first lightbulb (“Nearly 70 years before Edison, Humphrey Davy demonstrated an electric lamp to the Royal Society,”) that early reading does not accurately predict intelligence, and that cholesterol is not a strong predictor of heart disease. Of these three topics, none are intrinsically about the moral value of the subjects’ sense of self (though it is of course possible to moralise about health or parenting), none directly addresses their sense of how much agency they have, and, unless those in the MRI machine are parents of young children, only one provides an immediately obvious set of action-possibilities (whether or not to eat high cholesterol foods). In other words, these seemingly apolitical topics, which also happen to involve a relatively low interaction with subjects’ sense of self, agency, and action-possibilities, likely trigger relatively low dissonance discomfort, and subjects accordingly appear to be able to tolerate any discomfort by simply changing their views in a way that lasts.

On the far left of the graph are topics where it is likely that subjects found contradictions far more painful and worked to rationalise away new information. This is evidenced by the fact that subjects changed their views very little no matter what evidence was provided to them. It is also evidenced by the MRI scans which suggest different types of neural activity when one’s political beliefs are questioned compared to one’s non-political beliefs, which suggests different types of discomfort and different types of cognition for these two types of reasoning:

As in other MRI related studies of cognitive dissonance, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is especially activated, suggesting a specific regular biological presentation across individuals. Another piece of evidence within this study for increased dissonance on political topics is the rapidity with which subjects sought to address challenges to their existing views. The researchers measured how long it took participants to first indicate they had read political statements they agreed with, then indicate they had read the contradictory evidence to those statements, and then rate whether their views had changed. The results were different for political views compared to other strongly held views; the study found that:

On average, participants responded that they had read and understood the statements faster for the political statements...During the challenges, however, participants took longer to respond on the political challenges than the non-political challenges...When participants were asked to rate their belief in the statement following the challenges, their ratings for political statements were faster than for non-political statements.

In line with the premise of cognitive dissonance theory, which is that dissonance creates discomfort, it appears that subjects understood the political statements more easily, but were more challenged by thinking about evidence that contradicted their views when the issue at hand was political-suggesting that this contradictory evidence about political may have been more uncomfortable than contradictions to non-political views, and taken more time to process. Nevertheless, subjects were more quickly certain of whether their views had changed (and they had in comparison changed very little) when it came to political issues. All this suggests a fraught process of encountering evidence one might be wrong about political issues, and a rush to dismiss it. If more research in this area provides similar findings, this will suggest that cognitive dissonance is particularly common in political reasoning compared to reasoning about other areas of life. As a result, subjects may rationalise away contradictory information or form beliefs retroactively to justify their behaviour more when it comes to political questions than other issues. For all these reasons, dissonance theory is an excellent candidate for political analysis because it appears likely that it is a phenomenon that is especially prevalent when people think about their political beliefs..

Similarly, in the “real world”, research on rationalisation, (an effect of cognitive dissonance) has shown that people tend to shift their political views towards whatever their current status quo is. Research by Kristin Laurin, for example, has shown that “San Franciscans rationalized a ban on plastic water bottles, Ontarians rationalized a targeted smoking ban, and Americans rationalized the presidency of Donald Trump, more in the days immediately after these realities became current compared with the days immediately before.” For example, once a plastic water bottle ban was operationalised, San Fransiscans became in favour of such a ban, often although they had opposed it days earlier (and so on). This may be caused in part by people noticing their own actions in “going along” with such a change and adjusting their views to reduce dissonance between their views and their actions. Interestingly, these sorts of rationalisations seem most likely to occur when the political reality seems inevitable, and this may also indicate that subjects change their views to match an inescapable reality in order to feel less powerless. There is also evidence that individuals change their minds about political issues after they take actions specific to their own lives. So, for example, in “The Turnaway Study”, researchers followed people who had sought an abortion, tracking both those who received one and those who were denied one due to various technicalities (e.g. they often had miscalculated how far along in the pregnancy they were). The study showed that “Women who had been denied an abortion were more likely than those who had received one to say they had become less supportive of abortion rights (21% vs. 9%), while women who received an abortion were more likely than those turned away to become more supportive of abortion rights (33% vs 6%).” This too aligns with what one would expect from the literature about choice, dissonance, and rationalization and suggests that people’s experiences in their daily lives shape their political views, including and perhaps especially if those experiences are not under their control. Subjects likely experience dissonance when there is a contradiction between their beliefs and their actions and then often adjust their beliefs to match their (frequently unchosen) actions.

…

Of course, dissonance is not the only psychological mechanism at work when people cling to harmful political beliefs, but it is likely a core feature and therefore highly important as an area of study. Similarly, while dissonance is very often involved when people consider their political beliefs, that does not mean it is only triggered by political issues. Clearly there are instances where cognitive dissonance occurs in ways that are (at least not directly) political. For example, cognitive dissonance is commonly found in situations where people face e.g. addiction, a condition that is at least not immediately ‘political’ but, at least in the most immediate sense merely reflects a person’s struggle to not see themselves as dependent on substances, or perhaps to accept the contradiction between their claims that they are okay and the reality of their daily life. In this sense, cognitive dissonance is not inherently political; not every instance of cognitive dissonance is going to involve large-scale questions of power. Nevertheless, I suggest that it may be particularly relevant to people’s political beliefs than other areas, and that there are good reasons to suppose, from even the small amount of existing literature, that it carries a significant effect on political consciousness. In short, modern political subjects may, for the reasons above, be particularly susceptible to self-deception when it comes to politics because politics involves both their sense of self and their sense of agency.

—

More on this soon! I would love to hear your thoughts in the meanwhile. And of course, if you’d like to, you can:

More on the evidence for this some other time.

The third author on this study is the well-known philosopher, author, and neuroscientist often considered one of the “Four Horsemen of Atheism.” That I disagree with his views on many political subjects and am therefore made uncomfortable by appreciating his psychology study is arguably itself an example of cognitive dissonance.

N.b. In their supplementary materials the authors list the issue of “taxes on wealthy” as a political view (correctly, in my analysis) so I believe the graph I have carried over from their work has been colour coded incorrectly on that issue in error.