Do We Need New Ideas, or Better Influencers?

The work of reproducing society’s intellectual life is both disrespected and feared. It's actually a great art.

Several years ago, two friends asked me to review their book. They were men, a fact that will possibly remain relevant throughout this piece. I liked their book, or at least quite a few aspects of it. But wanted to warn them, before I pitched a review anywhere, that I felt the book, though valuable, was not original.

This mattered because the authors literally prefaced their book by insisting that it was not making the same point as [insert long line of other thinkers]. And I simply did not agree. Most of the things in the book were basically points other authors had made. That said, my friends had created a new conversation with the reader, a path that might convince a certain kind of bourgeois bohemian to sit up straight for a moment and think a little bit about politics instead of chakras or effective altruism.

When I told my friends this, they were… not pleased. No, they insisted, I had not really understood their work. Sure, their ideas sounded like a bit like Hegel or a number of psychologists, but something about their combination of thoughts was in fact entirely original.

This all might sound like I was rather cruel to my friends, but what I was telling them about their book is not an insult in my world. In fact, I have come to believe that, at least when it comes to writing about culture and politics for the public, we don’t really need new ideas. Instead, we need to do a better job of promoting, teaching and implementing existing ones. This latter task is often more difficult, and generally more important.

Surely—someone will object when reading this—we still need more new niche policy ideas? Maybe so. What about perspectives of marginalised groups that haven’t yet been published? Sure, I’ll make an exception here and there. But on the whole, the reading public already have many good analyses of the economy or mediasphere or gender, right at their fingertips. If we’re writing to help people or change the world, something else is required.

When I admit this view, I find it meets a lot of resistance. Everyone wants to find the exceptions. Many people can’t even imagine an alternative. The same anxieties came up frequently when I worked for an organisation called The School of Life, helping to write short videos of famous thinkers.

There were issues with these videos. But what interests me is how often people ended up digitally shouting back at us that nothing *new* was being presented—something the School regularly admitted. Yes, we’d say in the team I worked in. Nothing all that new is here; this is a psychoanalytic school with a philosophical bent, we’re simply doing our best to present ideas so that people will read them, and better yet use them. This was, I think, so unusual an admission that many couldn’t hear it.

Why is this point so tricky for many? Why were my two (male) friends upset by my analysis, and why, more generally, are people regularly itchy around the idea that writers and thinkers should spend a lot of time communicating the same ideas to the public, teaching and strategically targeting their message, rather than trying to come up with new concepts or a turn of phrase no one has ever coined before?

I think it has to do with social-reproductive labour and its status in our society.

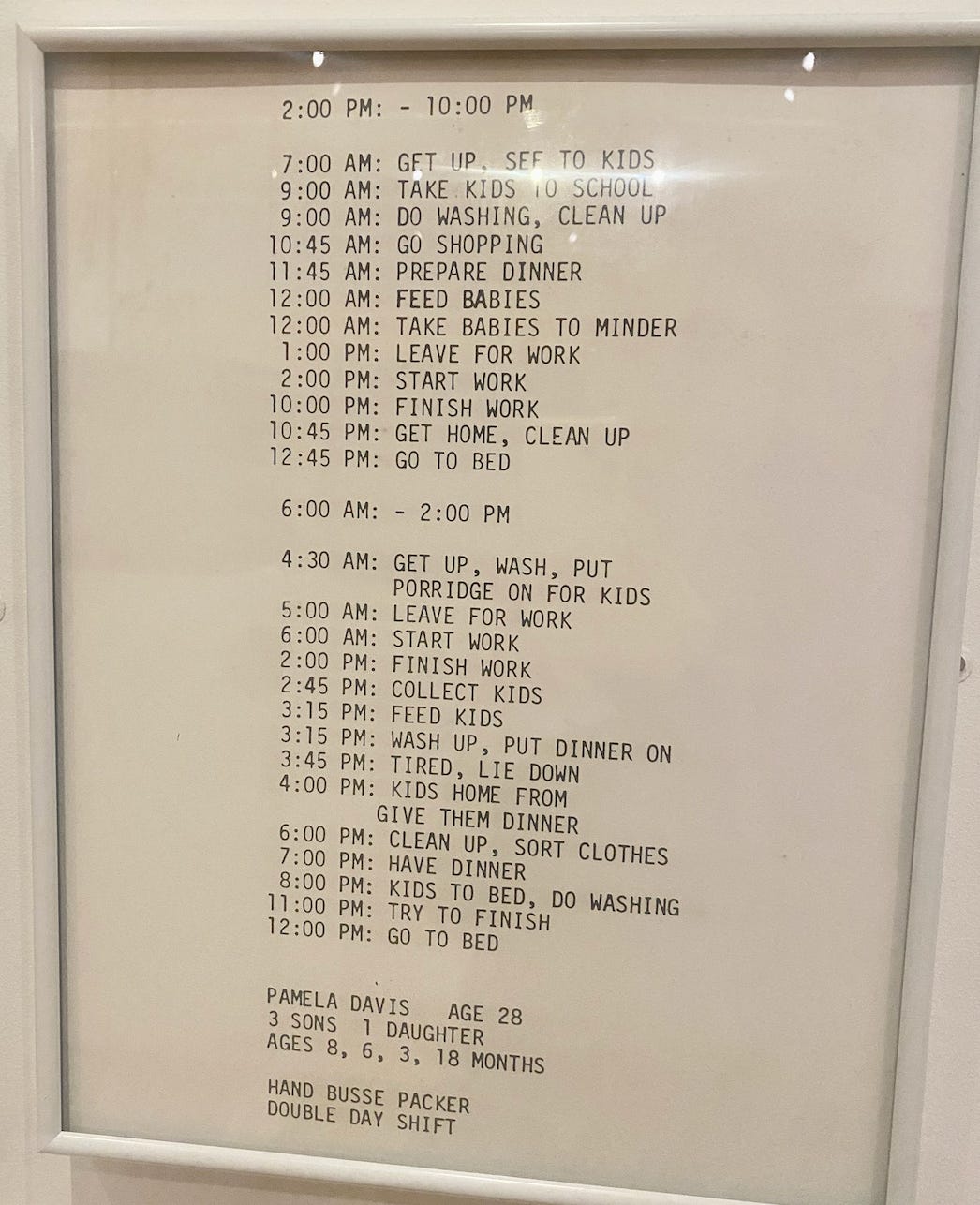

Yes, I know, it’s a clunky phrase. Bear with. In the Marxist feminist tradition, social-reproductive labour is the work that goes into maintaining the workers who, in turn, produce the goods and services that themselves create the excess value that becomes capital. Social-reproductive labour, the labour that creates not just people but ready-to-go-to-workers, has to do with not only gestating, birthing, and raising babies, but maintaining them even when they’re adults: cooking and cleaning and washing and healing, and even tending to the myriad small sad and angry feelings that working people tend to have at the end of each day of work, all so that they can go back the next day and pick up the tools of their trade again. It also has to do with teaching people the things they need to know, from culture to emotional sensibilities to practical skills (after all, they wouldn’t be useful workers without these). Even today, many people, especially women, work a double shift, earning a wage and then coming home to do another set of long hours offering care and sustenance to others.

This social-reproductive labour is undervalued both in terms of prestige and money. The same is true in the waged economy, of course: those who do jobs that involve social reproduction, people like teachers and nurses, are paid hardly anything at all when one considers the incredibly taxing long hours and utter devotion required. Lip service may be given to the value of these jobs, but in practice they go under-supported and under-resourced.

What I’m going to suggest now is that there is a form of work that is both social-reproductive and intellectual, which we might well call intellectual social-reproductive labour. (Sorry again for the jargon!) It is the work we do as a species to shape each other intellectually in order that the next generation can engage in complex thinking. After all, to have certain kinds of workers (nevermind members of say, “the public sphere”) people must come to understand tricky concepts or be able to conduct relatively rigorous analysis. The university is perhaps the primary place where this kind of intellectual work happens in a formal way for adults, though of course there are other places too—and one of these, increasingly, is social media.

As is the case with its non-intellectual equivalent, intellectual social-reproductive labour is generally disrespected and poorly paid compared to other forms of intellectual labour. Our society pays teachers poorly, and pays those who primarily teach in universities worse than those who primarily research. There is a sort of reverse premium on the intellectual labour that produces the next generation of thinkers, even though other more “productive” forms of intellectual labour rely on it.1

Theorists have noticed this paradox about all sorts of social-reproductive labour, and they tend to argue about why this is—is it mostly about the oppressive nature of social structures like the patriarchy, which are designed to in effect trap and coerce the social-reproductive workers? (Is it, in other words, that both those who mother and those who adjunct have few good options)? Is it that the work is so rewarding that people are willing to do it anyway (few mothers would abandon their children, teaching feels meaningful)? Is it that it is only the excess production in capitalism that is seen as valuable, because it creates the new literal capital (is it that daddy’s job, or investment banking are historically seen as “productive” because these roles appears to be what creates profit margin, unlike social-reproductive labour)?

The answer is probably all of these, and more. There are at least two extra reasons for this distinct valuation of social-reproductive labour. I’ll turn to these now, and then outline some related challenges that arise for those of us trying to speak to the public about culture and politics.

It’s not just that our culture disrespects social-reproductive labour. In some curious deep sense, we fear it: both what it does to us when we care and when we are cared for.

Firstly, we fear what happens when we care in this way: many of us are afraid to spend time helping others exist and grow, lest we doom ourselves to apparent obscurity, and hide ourselves from the esteem of the world.

Secondly, we fear what happens when we are cared for in this way: many of us fear the power of the social reproductive process of shaping the other; its hidden enormous influence, its inescapable asymmetry. There is something that is a bit coercive even in good care, including teaching and the shaping of intellectual sensibilities, and that is frightening even when it is probably necessary.

Let’s turn to these two points in turn, visiting what first Marx and then Nancy Fraser charmingly termed the “hidden abode” of capital, that secret place where people are produced and reproduced.

First: in the hidden abode, one's labour is largely unrecognised a lot of the time, and one's name is consigned to the dust. For social reproduction is usually a relatively thankless, hidden sort of labour. You don’t get to put your name on what you create (whether that’s a child in patriarchy or the sensibilities of undergraduate students). Those you help often don’t even thank you, because you become part of the background, taken for granted (they might even show up in your inbox or office hours demanding you treat them differently). As the Marxist feminists point out, we’ve created a world where the work involved in care and love isn’t even seen as work, and usually isn’t seen at all. Sure, people sometimes remember their professors with deep appreciation, but often they don’t. In contrast, who doesn’t want to see their name on a book, reviewed in the newspaper or at least entombed in a library forever? Frankly, it’s no wonder many, perhaps most people prefer research roles in universities. No wonder too that my friends wanted their book to be seen as original, memorable, cited forever. It’s more prestigious, better respected, and better paid, to be a supposed “original thinker.”

Plus with publishing comes the fantasy of immortality. If we can’t live forever, isn’t it beautiful to think our ideas will?2

Of course, this could change. Whether this work will always be so thankless and forgotten as influencers become more prevalent in the sphere of intellectual social reproduction is also an interesting and as-yet-undecided question. For now, however, the fear understandably remains.

Second: there’s the other tricky matter: the aversion many of us feel about the power dynamics involved in social-reproductive care. For there is a kind of uneasiness, even fear, that people have about receiving care from someone, especially someone who knows things they do not. It lingers when we encounter doctors and nurses, but also parents and teachers.3 Perhaps even with “good” mothers and teachers. Being cared for makes us vulnerable. And when it comes to intellectual matters, being cared for in a way that makes us see the world differently makes us even moreso.

This wariness is not necessarily misplaced. What the carer does for us, out of generosity and necessity, involves an element of intentional performance and even trickery, even if directed towards positive ends. The parent treats the child as if they are capable of using a spoon, reading a book, deciding how their life will unfold. They feign a kind of interest and surprise regularly to help the child learn how to be interesting and surprising. In so doing, they make everything they pretend a little more true. Indeed, much care throughout life takes an unequal and even performative or manipulative shape. No wonder social-reproductive labour is often resented, and it really is. Children constantly resent parental care, even though much of it is required (which is not to deny the reality of bad parenting and abuse). Even in adulthood, women often continue to socially-reproduce the men in their lives, feeding and nurturing them with words and care as much as food, creating their social world, doing more to keep relationships alive, and of course preparing the men to go back out in the world and work. This too leads to resentments: girlfriends and wives’ requests and demands are frequently seen as nagging or irrational.

This is the bitter pit in the sweet fruit of care: the discomfort we might feel about it is rarely far from resentment or disdain.

I will not dally with this painful point about the resentment often given to carers here. In a way, both the carer and the cared-for are right to feel as they do; care is not love (as bell hooks puts it, more on her soon) and it is scary.

The point for now is this: it can feel bad and unfair to receive care, especially when one party is simply not in a place to understand why that care is happening the way it is. This is just as true when it comes to making people think and think differently. No wonder there is always a hysterical fear of the college professor or a certain kind of influencer as the corrupter of the youth.

All this complexity is just as true in social-reproductive writing, where the writer isn’t just imparting some supposedly original idea but is instead trying to make an idea a part of how the reader thinks about the world, so that they can do intellectual labour of their own.

To overcome the anxieties of the reader about the change they are going to experience in themselves, the wise or crafty intellectual social-reproductive writer does much of what a mother or girlfriend does, even if they would never want to think about it that way. They try to predict the expectations and attention and the reaction of the reader. They fill their writing with little charming hooks and speak to the reader’s existing interests. (Perhaps you can see now why I often view social-reproductive intellectual labour as at least as difficult, and at least as difficult to get right. I really did not mean to insult my friends!)

The wise reader rightly fears the wrong sort of shaping of themselves, the wrong relationship with the writer. This is why the wrong tone, even a single poorly-chosen word, can cause a reader to put down a piece forever. That is the real hermeneutics of suspicion, a paradoxical one when it comes to reading to learn: one does not want to be lectured, or in any way tricked or coerced, even if one secretly longs to be transformed. One wants to be cared for, inspired, given clarity, understanding, conceptual tools, even made more powerful in the world; but also receiving this kind of care, even care for our intellectual life, is frightening.

If it is scary to write and be resented, and scary to read and be potentially transformed, how then can we understand social-reproductive intellectual labour, and what it looks like when it “works?” One possible model, controversial though it may be, is that of the influencer.

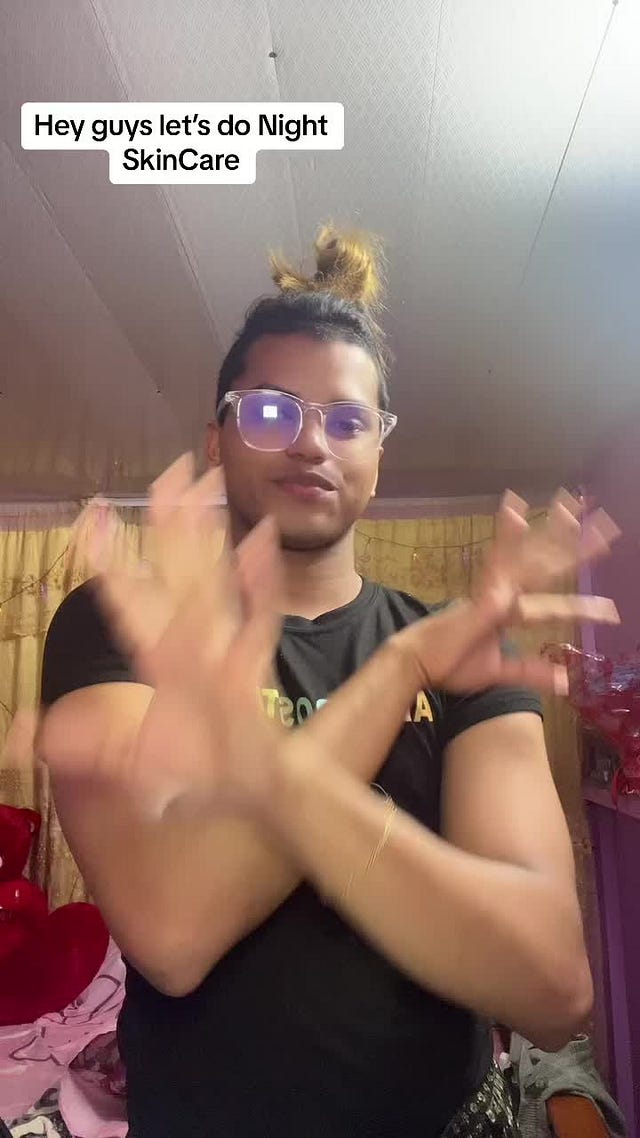

Interestingly, influencers are rarely trying to be truly novel. Many influencers (and here I’m going to turn specifically to the type engaged in making video reels as my main reference) explicitly work with remixes, both of songs and scripted dialog. Most successful influencers are terribly unoriginal, and interestingly they don’t care, quite the contrary. Firstly because mimetic and repetitive content works very well, for algorithmic reasons, and also because it turns out novelty is usually not what their viewers are looking for.

What are their viewers looking for if not new ideas? Interestingly, a lot of it is a type of social-reproductive care that can be provided parasocially and at scale. Influencers are creating remarkably popular and engaging materials of social reproduction, teaching people how to care for themselves and be in a certain way. This includes how to apply makeup, parent, cook, clean things efficiently, manage relationships, and do “self care”. The influencer is in many ways a stand-in for the mother, partner, and best friend that we all might need at some point but not be able to access for whatever reason. And of course, they are not cleaning or cooking for you directly; they’re giving you inspiration and information instead; they’re changing your brain, whether that’s with regard to your mood or your understanding of risotto, attachment styles, or late-stage capitalism. Their work is thus always social-reproductive and cognitive, and sometimes intellectual.

This touchingly suggests that none of us are ever really getting enough of this specific kind of instruction and care, that none of us are ever really feeling ready to go about the business of being human. It also suggests this set of needs is always an “in” to an audience, one that can be used for good or ill.

I mentioned that it might matter that these two friends were men. I think it does because I think the gendering of the production of “new ideas” remains present in our society in a profound and problematic way. To want to write to transform your reader rather than assert something novel is still a sort of “feminine” move, in that it sets out to establish the other as an agent, not oneself. To write “for the public”, hoping they will take up thinking differently, is, oddly, to align yourself with the mother and the nagging girlfriend or wife, with the influencer, with the teacher, with all those giving instructive care. I am asserting this point about gender descriptively and not prescriptively, of course; the gendering involved in nearly all social-reproduction is alarming and should be. Notice how the masculine option of writing “new ideas” is seen as both objective and more impressive, while the social-reproductive female labour is seen as potentially dangerous, even as many of its most difficult aspects are both necessary and inescapable.

To really think differently about all this, I suspect we’d have to change our very understanding of the term productive. If I spend all day making memes that teach people weird nerdy concepts, many people in my life would not see that as productive. Even blogging is likely to be seen as less productive than working on my book manuscript. There is a hierarchy to it all one that more or less tracks with how much writing is seen as, well, teaching others and/or entertaining them vs. creating new ideas.4

Industries too would have to change. To this day the publishing industry seeks to market intellectual writing as novel to a both humorous and unhelpful degree. There is a constant emphasis on what is supposedly groundbreaking and original, even though most authors would admit (even if only to their closest after a few glasses of wine) that the book is a mashup of their most beloved thinkers with a couple of modern references. Or sometimes even the authors themselves become convinced of the need for novelty, such that each generation becomes convinced they are orphaned intellectually and need to rewrite all things again, often without realising how many shoulders they are standing on.5

Instead of new ideas, writing for the public today (especially when it comes to culture and politics) should be focused on something else: a moment of trust that can only happen when the writer is, well, humble and no longer fears the obscurity of their labour, and the reader no longer fears they are being manipulated. A certain kind of near magic must happen: trust must be built. I rarely see this fully functioning in my field of social-political commentary, but when it does happen, it is incredible. People who don’t really have any political affiliation in common with David Graeber, for example, will read his books with gladness and alacrity, and come to a new way of seeing the world. When bell hooks died, her book on love suddenly accomplished a similar feat, at least for a select portion of the population.

What’s most remarkable about these books is not any single idea within them. Indeed, critics have often complained at how much within them is not new at all. But these critics are missing the point: what the books do is establish a relationship with the audience, who trust the writer enough to reconsider mostly old ideas about (say) debt or patriarchy or authority, such that eventually the audience is transformed.

There are probably no easy rules for creating this relationship, this “magic”, but it is interesting to consider the commonalities. I do not think it is mere happenstance that both Graeber and hooks are absolutely alive on the page, fully present and themselves, clearly stubborn unrepentant weirdos utterly unconcerned with pretense. They are willing to “bite” at any subject, but never willing to punch down. They are not just readable, but happy to show their audience most of their rhetorical moves along the way. They are interested in seemingly mundane questions that are probably alive in the lives of the reader and happy to repeat themselves over and over again (as good teachers generally are). They are able to do this while keeping everyone’s attention because they are (as my wonderful agent likes to put it) “good company on the page.” And of course, they both take reader seriously, never alienating their trust by dumbing down, always assuming their readers could go with them wherever they wanted to go, whether it was a fierce critique of everything under the sun or a very funny joke. When I write, I think about them a lot (which is not to say I manage their craft).

I don’t want to say that Graeber and hooks were influencers because this is to take the kind of position common in the first phase of the “galaxy brain” meme. It’s just too basic. But I think it is true that Graeber and hooks were at some level uninterested in a certain kind of novelty, that they were not really engaged in the production of new ideas. Instead, they were doing something that good influencers do: they were focused on maintaining a relationship with their audience. After all, the influencer is never really giving you makeup tips first and foremost; they’re doing what they do to win trust and build a relationship as they teach some kind of care. Successful influencers know one’s relationship with an audience comes first and needs maintaining and adjusting again and again and again (like all relationships.) It’s a real art. It’s also very powerful.

Influencers have perfected the art of making others feel seen and connected to them, even in their usually-not-intellectual spheres. “Listen, guys” they intone in an empty room, to their devices, and millions feel heard and seen.

These days, if I’m tempted to worry about originality, I think about social-reproductive labour and how it is undervalued, I think about Graeber and hooks, and I tell myself:

Sure, you could write something original. But why not do better? Why not write something honest, helpful, good?

Will this continue to be true for influencers who do this kind of work? Let’s see…

I am far from immune to this idealistic fantasy!

The distinct power dynamics involved here are played out over and over in pornography, if one needs an example of some evidence of this assertion!

You may find yourself saying, isn’t this a bit of a false dichotomy? Doesn’t the professor find his best ideas so often come from his students, from lecturing? Isn’t an idea reinvented every time it is taught?

Perhaps at some spiritual level, but that appears, I’d suggest, more at the level of the person doing the teaching than the market that rewards them.

In line with this point, thanks to Max Haiven for chatting with me about this; the point I am making here is not original.

"when it comes to writing about culture and politics for the public, we don’t really need new ideas. Instead, we need to do a better job of promoting, teaching and implementing existing ones."

This is great. And it's also how I feel about technology and climate mitigation. The tech exists, people! (waiting for a few advances in battery technology) - thanks Sarah for your wise and provoking article

Thought provoking piece, thank you. I think the drive to be (and be seen as) original illustrates a deep problem in our society about individualism and hero-worship as contrasted with collaboration and community. I also wonder if we often seek 'the answer' rather than being prepared to grapple with complexity and unknowing.